The vast majority of ex-libris produced over the centuries in Britain have been part of the jobbing work of trade engravers, and many towns had an adequate artificer. Styles and ornamentation altered from time to time, and the form of these – in the absence of other evidences – are a useful guide to approximate date. Thus, for instance, the simple spade shield, sometimes with a festoon and/or wreath, succeeded the convoluted Chippendale or rococo compositions of the mid decades of the eighteenth century and predominated during its last quarter. For much of the nineteenth century so called “die-sinker” armorials, often engraved on steel, became the tedious norm. Anyone who was or fancied himself as a “somebody” tended to enhance his books with a bookplate. Most were armorial. but un-armigerous folk were not deterred from adopting unentitled achievements. Firms of heraldic stationers flourished, and it is ironical but understandable that the period of most widespread ex-libris usage witnessed also the nadir of artistic panache. Few areas of graphic art can have seen such early sublimity unmatched subsequently, for Durer and the German “little masters” of copper engraving remain for many of us the greatest masters of armorial depiction.

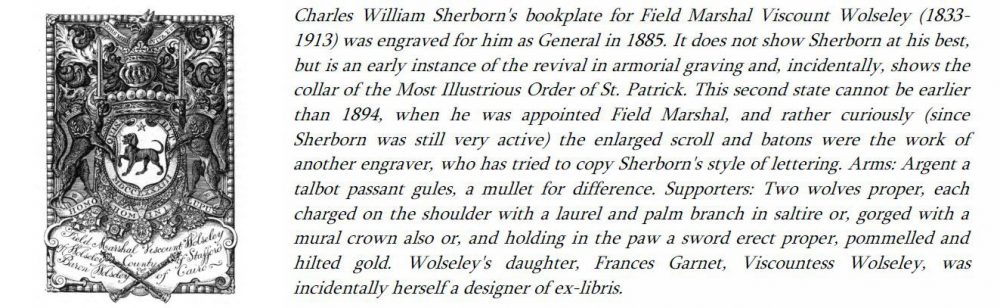

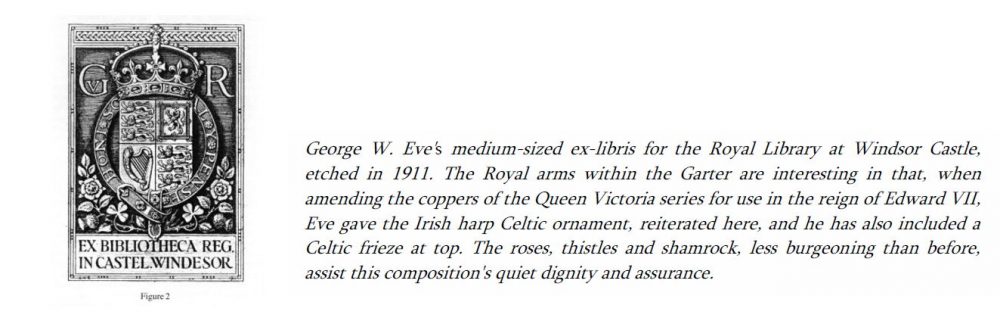

A long-needed renaissance of copper-engraved bookplates in Britain was principally established by Charles William Sherborn (1831-1912) who. after a tentative start, devoted himself predominantly to armorial ex-libris and came to be called the Victorian “little master” (Fig. 1). George W. Eve (1855-1914) became his counterpart in the medium of etching, and produced, for instance, the excellent series of three bookplates for the Royal Library at Windsor Castle used towards the end of Queen Victoria’s life and through the reigns of King Edward VII and King George V (Fig. 2). Edward VII’s were merely the Victoria ones adapted by reworking the original coppers, but the George V ones demonstrate Eve’s ability to convey a sense of majesty with greater linear economy than the earlier series evidence. Other excellent copper engravers of bookplates of that period in the same mould were members of the Wyon and Downey families and Acheson Batchelor, but there is not space to illustrate their work here.

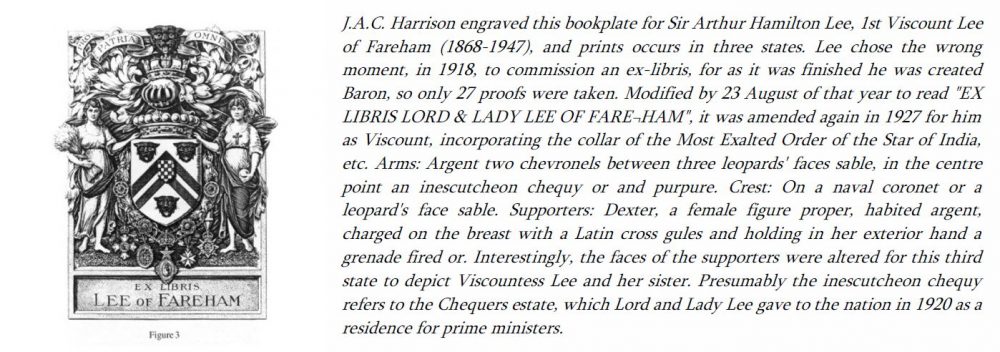

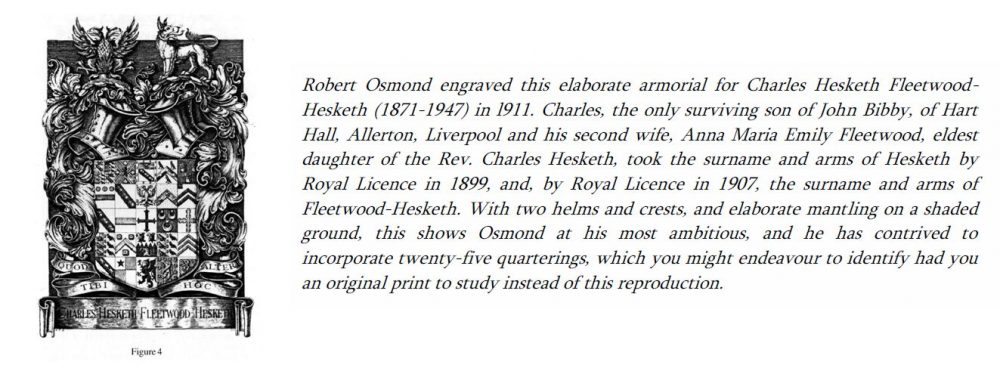

It was inevitable that top-class London booksellers and stationers should realise and exploit the possibilities of ex-libris production for the gentry, on account of their clientele and since between 1896 and 1928 their employee William Phillips Barrett ran that department with great vigour and enthusiasm. The extent to which he personally engaged in design has been a matter of debate, but he deserves acclaim as an entrepreneur. Barrett engaged at least five first-class engravers as and when required, but by the terms of their contracts they worked anonymously. Charles Bird, John Edward Syson and George Ernest Vize were artist-craftsmen who set the ball rolling and much assisted definition of what became the house style, but their achievements were eclipsed by those of John Augustus Charles Harrison (1872-1955) and Robert Osmond (1874-1959). Harrison was also a dis¬tinguished stamp and banknote engraver who sometime worked for Waterlows, and in the writer’s view the design and execution of his armorial bookplates is the best of its period (Fig. 3), as was the skill on a minute scale which his pictorials – and banknote and stamp portraits – evidence. He engraved over 350 ex-libris, many of them later and independently, for in 1908 he parted company with Barrett because of the anonymity clause and since “WPB” was ever keen to claim major credit for himself. I have produced monographs on Harrison and on Osmond, his successor, who differed from him in several respects. Osmond didn’t, as he put it, “care a zap” how his engraved bookplates were signed so long as he got the business; he was often less felicitous in pictorial depiction; and he devoted most of his life to ex-libris making, with over 500 to his credit in all. (Fig. 4). Osmond continued to engrave bookplates for Bumpus long after Barrett’s retirement and then independently until not long before his death.

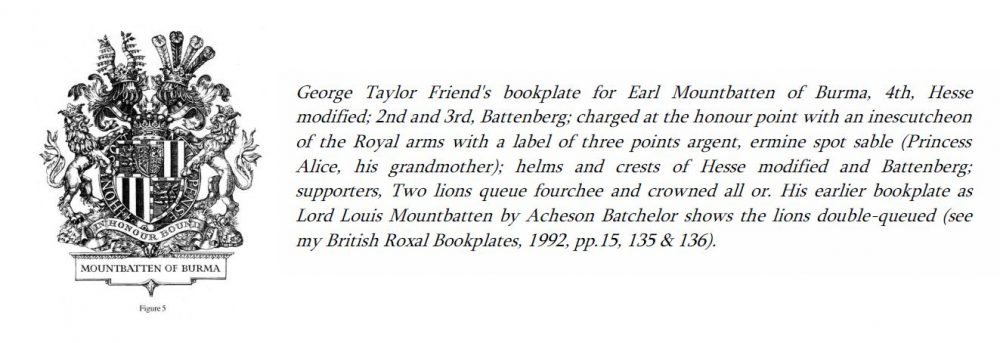

Frank George House was Barrett’s counterpart at the Knightsbridge stationers Truslove & Hanson, and he employed Harrison, Eve, George Taylor Friend, Henry J. Haley, J. G. Potts, Alfred Sparkes, F.H. Tebay and probably others – like Bumpus’s anonymously – and seems to have had a closer hand in design. Determining which engraver produced what and for whom is by no means always easy, but George Heath Viner produced checklists for Sherborn and Eve, the writer has documented Harrison and Osmond’s work, and Philip Beddingham served Friend similarly. George Taylor Friend (1881-1969) taught at the Central School in Holborn and from 1912 had his own workshop in Holborn, where he engraved over 500 ex-libris of high quality during the course of over half century. Some of his work was for Smythsons, the distinguished Bond Street stationers who still accept bookplate commissions (Fig. 5). Friend’s pupil Leo Wyatt likewise carried on the armorial tradition with distinction. Lord Badeley was an amateur etcher of bookplates, but his compositions can be of unequal quality, unlike the small number of magnificent armorials by Stephen Gooden, which included the Windsor Castle series of three for King George VI and Her Majesty the Queen. Gooden and Badeley were probably always freelance, however.

Without doubt we owe a debt of gratitude to top London stationers and booksellers, etc., for the full flowering of the heraldic bookplate’s renaissance in Britain during the past century. There are several copper-engravers still producing ex-libris, including the excellent Stanley Reece, but it is nevertheless a much diminished phenomenon. Copper engraving is scarcely taught in the schools nowadays; it is a time-consuming and therefore costly procedure; and the amount of money people are prepared to spend on a bookplate decreases. What I see as the College of Arms tradition of process-produced plates is sound heraldically, but one could wish for a little less chastity of design and more exuberance, not least in the matter of mantling. As I’ve tried to show, today’s practitioners do no need to look far back for the sort of inspiration that could be transforming.