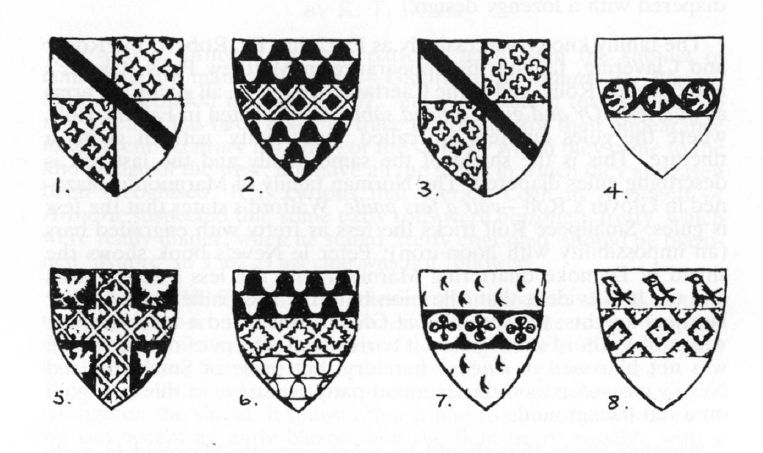

Fretty and paillé arms: Fig. 1. Clavering 2. Philip Marmion 3. le Despenser 4.Jehan de Clere 5. Thibaut de Mailly 6. Jehan de Tongres 7.Henri de Ferrieres: 8. Wilhelm Schillinck von Bomheim.

Fretty and paillé arms: Fig. 1. Clavering 2. Philip Marmion 3. le Despenser 4.Jehan de Clere 5. Thibaut de Mailly 6. Jehan de Tongres 7.Henri de Ferrieres: 8. Wilhelm Schillinck von Bomheim.

The above forms of heraldic patterns have been the subject of comments by many authorities: Galbreath in Manuel du Blason, Stanford London in Aspilogia II,1 etc, as eastern textiles, but no real attempt has been made to trace the reason for their appearance in thirteenth century heraldry, or the steps by which they came to the knowledge of the west; nor have all the forms in which they appeared been recognised. It is curious that Gerald Legh in Accidents of Armorie suspected that some early rolls were blazoned ‘fretty’ which were really diaper, when he stated ‘fretty engrailed’ should be blazoned ‘dyapre’ in 1562. This clue was not followed.

We know the Franks strengthened their wooden shields with a trellis of hoop-iron, which was readily available due to the coopers’ flourishing industry. At the birth of heraldry these trellises, painted in a contrasting tincture, produced fretty. As its purpose was to strengthen the shield, it follows that it had to cover the whole field: in early blazon a field fretty might have a chief or other ordinary over, but no shield-maker would construct a shield with a trellis upon a fess, chevron or chief. This would remain a custom until the origin of the real fretty was forgotten; its origin was remembered during the thirteenth century and it was not until the turn of the fourteenth century that ordinaries were adopted with fretty over. Therefore thirteenth century armorials blazoning ordinaries as ‘fretty’ are likely to be a form of diaper-textile and investigation of both painted and blazoned rolls tend to support this.

The family known successively as FitzJohn, FitzRobert, FitzRoger and Clavering, familiar by appearance in Matthew Paris, Glover’s and Camden Rolls, and in the Caerlaverock Poem, all giving the arms as quarterly Or and gules a bend sable, also is listed in Falkirk Roll, where the gules quarters are called ‘gules fretty’ without giving a tincture. This is the shield of the same family and the last roll is describing gules diapered. The Norman family of Marmion is blazoned in Glover’s Roll as vair a fess paillé. Walford’s states that the fess is gules: Smallpece Roll tricks the fess as fretty with engrailed bars (an impossibility with hoop-iron); Peter le Neve’s book shows the shield of Dymoke quartering Marmion with the fess lozengy gules and or. It is evident that Marmion bore the fess paillé, as did other Norman knights: the compiler of Glover’s blazoned it correctly; the writer of Walford’s recognised it correctly as a form of diaper, which was not blazoned in English heraldry, but those of Smallpece and Neve’s misunderstood the diamond-pattern diaper, in this case gold on a red background.

Another shield that should be more correctly blazoned in early rolls is that of le Despenser: Matthew Paris, Glover’s (making the whole shield fretty), Camden, Falkirk Rolls and the Caerlaverock Poem all make quarters two and three fretty; between 1200-1300 these must be diaper. Similar confusions exist in early French armorials like Bigot and Wijnberghen.2 Normandy shields like that of Jehan de Clere are blazoned correctly as ‘paillé’, but the descriptions of a cross fretty argent (Thibaut de Mailly); the fesses fretty of Jehan de Tonges and Henri de Ferrieres (both or), and of Guillaume de Buir (argent) cannot seriously be accepted as fretty. They must be diaper. This is supported by Bigot Roll which ascribes to Wilhelm Schillinck von Bornheim Or a fess gules fretty argent with three martlets of the second in chief. 3 As even a field fretty is virtually unknown in German states, except along the western border, this must be another example of a herald listing a lozengy diaper as ‘fretty’.

When studying seals, diaper does not appear on twelfth century examples with a single exception: the chevronny armorial seal of a lady. Rohaise de Clare, Countess of Lincoln, with alternate diapering.4 By the thirteenth century seals regularly depict the field, or a part divided by a partition-line, with a diamond-shaped pattern.

Colour had been applied to shields in the ancient cultures of the Mediterranean area, again in classical Greece, and on actual shields excavated from Viking burials, but there was no precedent for the use of fabrics and furs in early mediaeval heraldry. What gave rise to their employment? The Byzantine Empire, at first in North Syria, later in Constantinople and Sicily, was the source of luxury fabrics,5 a knowledge inherited from contact with Asiatic races. Silks, satins, muslins, brocades, damasks and samites woven with striking repetitive designs in contrasting shades or in gold thread were produced in quantity. Europe in the early Middle Ages was an ‘open’ civilisation,6 with trading, cultural and intellectual links between all countries, east or west. Charlemagne exchanged letters and gifts with Haroun al Raschid, Caliph of Baghdad. Byzantine textiles were found in the tomb of Charlemagne at Aachen, and in the grave of St. Germain at Auxerre. Northern scholars studied Greek and the Classics at Moorish universities in Spain.

These Byzantine textiles with ‘allover’ designs fascinated western nobility and they were eager buyers. The Greeks called these fabrics διβαφος (dibaphos — two colours)7 and the French merchants at the great fairs did their best to preserve the sound as ‘diaspres’, which was later turned into mediaeval latin as ‘diasprus’.

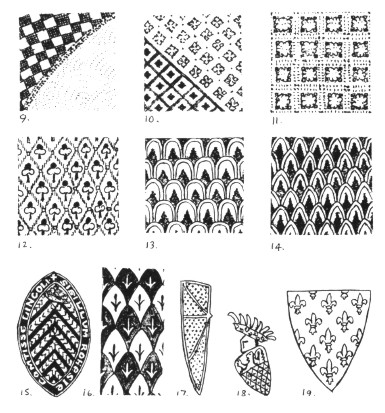

Diaper patterns appear as a background in scenes like the enamel plaque of 1151 above the tomb of Geoffrey d’Anjou at Le Mans, where the design is spearhead scales each enclosing a simple fleurs de lys in alternate silver and blue. 8

By early thirteenth century these tourneys and the pageants became great colourful spectacles and the contestants began to employ luxury horsetrappers, shields and embroidered surcoats. The battered combat shields were too crude for these fashion parades, so by early thirteenth century they are shown covered by rich brocades and designed eastern textiles. Having adopted the principle of textile covering of the shield, the obvious course was to extend the idea to utilise the two luxury materials already in common use for garments of the nobles — the alternate light and dark pelts of the grey squirrel, known as vair, and the white fur ermine. The two furs come into heraldry in the early thirteenth century. It is significant that the armory of the Spanish and Scandinavian lands which had no contacts with the trade of the eastern Mediterranean made no use of diaper, vair or ermine in thirteenth and fourteenth century heraldry.

The earliest diaper textiles were the repetitive designs from the Syrian looms: these are familiar as the diamond shaped diaper and were frequently of great length. Later the Constantinople workshops produced fabrics with a medallion motif enclosing lions,9 double or single eagles, fleurs de lys, etc., mostly of short length and often bearing the pattern in gold thread. This was particularly popular in Normandy in azure, vert and more rarely gules, and was blazoned as ‘paillé’. Examples are attached of Byzantine fabrics and western shields showing both diamond and medallion textiles in use.

The evolution of diaper over the centuries

The evolution of diaper over the centuries

Above: Fig 9. Robe of a female Saint in mosaic at St. Appolinare. Ravenna. 561 A.D. 10. Robe with Byzantine reversed patterns, figure of a saint. St. Demetrios at Salonika, pre-700 A.D. 11. Robe of Emperor Constantine, mosaic. St. Sophia. Istanbul, c. 1030 A.D. 12. Byzantine woven textile, St. Serratus. Maastricht. 1000 A.D. 13. Byzantine purple silk shroud (the finest extant), tomb of St. Germain. Auxerre. showing featherwork on golden eagles’ breasts; 14. The same, on eagles’ wings. (Both 13 and 14 inspired the heraldic diaper forms of France) 15. Seal of Rohaise de Claire, spear-head diaper c. 1150. 16. The same on background to plaque over tomb of Geoffrey d’Anjou. le Mans Cathedral 1151. 17. Diapered Shield on effigy. Temple Church, c1218. 18. Seal of Herren zu Eltz, argent base diapered, late 13th century. 19. The fleur-de-lys of France ancient.

The first heraldic use of diaper, in general, followed the lozengy design, with occasional employment of the spearhead pattern; later the medallion form came into use: by the second half of fourteenth century the Byzantine ‘trailing vine’ type appears and continued to be used on seals, tombs, stained glass, etc. as an art-form long after heraldry had ceased to be used in warfare.

Figured silks like the Auxerre shroud of c. 1050 with repetitive single eagles in gold on a purple background show the eagles’ breast feathers woven as round-topped scales and those of the wings as spearhead shapes. Rohaise de Clare’s seal is based on the latter, but the round-headed type when turned upside down formed the design blazoned in French armory as ‘papelonné’, which was always a gules background with the pattern in one of the metals.10 The compiler of Bigot Roll, quoted by Stanford London (Aspilogia II, Appendix II), described No. 286, the Comte de Sancerre (a cadet of Champagne) as ‘l’escu d’azur palelonné d’or a une bende d’argent a iij listiau d’or a une molette de geules en la bende’. Apart from obvious points like the error of three cotices for two, and that the compiler had not mastered a concise method for blazoning ‘azure a bend argent coticed or charged with a mullet gules’, he was apparently ignorant of papelonné being confined to a gules background. The field was evidently azure diapered or. This is confirmed by the blazon in Walford’s Roll, No. 42, ‘Le comte de Chaumpaine d’azur a une bende d’argent a custeces d’or diasprez’. Stanford London (Aspilogia II)11 misunderstood this as indicating only the cotices were diapered: as these were the most insignificant charges on the shield such decoration would be invisible. It is clear that the adjective ‘diasprez’ applied to the whole shield and the scribe is describing a similar shield to that in Bigot Roll above. London’s further comment on the enamelled arms on silver at All Souls Oxford, showing dovetailed cotices is a craftsman’s attempt at producing the double interlocking cotices peculiar to the comtes de Sancerre after 1288 12, when they tried to reproduce the single cotices potent-counterpotent introduced by Edmund of Lancaster as Comte de Champagne up to 1284.13

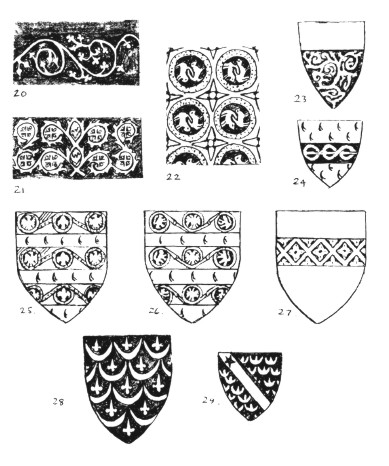

In conclusion, the evidence suggests that diaper was more widely employed in early heraldry than thirteenth century rolls record. This was due to the heralds not always recognising diaper as such, but mistaking it for charges. One case of this nature is the arms of the Normandy family de Fontaines, given as a fess plain gules and in other instances as charged with three circular buckles (fermeaux) or.14 Undoubtedly this was originally a fess paillé gules; so diaper and paillé were the same fabrics, but the former was not considered as an alteration to a shield nor normally blazoned in any European country, while the latter, a term confined to the armory of Normandy families, was always blazoned, and if necessary, could be used as a difference to denote another member of a family who bore an ordinary plain. These de Fontaines shields had originally shown the medallion form of paillé gules: this was unfamiliar to an early herald who blazoned it as three fermeaux: with the passage of time this error was perpetuated as buckles.

Byzantine trailing vine and medallion patterns, and papelloné:

Byzantine trailing vine and medallion patterns, and papelloné:

Above: Fig. 20. Dyed textile border. “Triumph of Dionysos”. the Louvre 5th century. 21. Embroidery on dalinatie,the Vatican, 15th century. 22. Tunic of (Admiral) Apokanos. MS Bibliothèque Nationale. Paris, Gr. 2144. 23. Arms of bishopric of Lausanne, fresco in cathedral c. 1350. 24. Arms of Giullaume de Fontaines. 25. Guillaume Tesson. 26.de Brisard. 27.Guillaume de Brin. 28. Papelonné (eagles feathers upside down) on arms of de Ronquerolles, Armorial Montjore-Chandon 1450. 29. The same on arms of Sancerre.

A similar mistake occurred in the case of the city of Liverpool. From the thirteenth century its council used a seal bearing black eagle of St. John, patron saint of the town’s church. The seal was badly engraved, showing the bird passing to the dexter with an elongated beak. In the nineteenth century, the council applied to the College of Arms for a grant of arms, sending an impression of the 600 years old seal. The heralds were unable to identify the bird and, as Liverpool was a seaport, assumed it must be a sea-bird; therefore they granted the city argent a cormorant proper, which remains their shield. However, later, when the Bishop of Liverpool was granted arms for his See the mistake was recognised and the arms of the bishopric included the black eagle passant to the dexter with a nimbus around its head.

Notes

- Aspilogia II, p. 164.

- Paul Adam-Even: Le rôle d’armes Bigot, 1254. A.H.S. 1940 and L’Armorial Wijnberghen, XIII c. A.H.S. 1951.

- Arm. Bigot above. No. 60.

- Archaeological Journal 1893. H. Round: Introduction of Armorial bearings into England: and Birch: Catalogue of Seals in Brit. Mus. vol. 3. plate 1.

- D. Talbot Rice: Art of the Byzantine Era.

- For the change from ‘open’ to ‘closed’ Middle Ages, see Freidrich Heer: Mittelalter, Vienna, chap. 1.

- Liddel and Scott: Greek Lexicon.

- A. R. Wagner: Heraldry in England, coloured plate 1.

- Talbot Rice. op. cit.

- L. Jéquier and D. L. Galbreath: Manuel du Blazon, p. 97.

- Aspilogia II, p. 164.

- Sancerre adopted the double interlocking cotices 1288 (A.H.S. 1952).

- Coat of Arms. vol. X. No. 80. pp. 261. 257.

- Larchey: Ancien Armorial Equestre de la Toison d’Or, section Normandy.