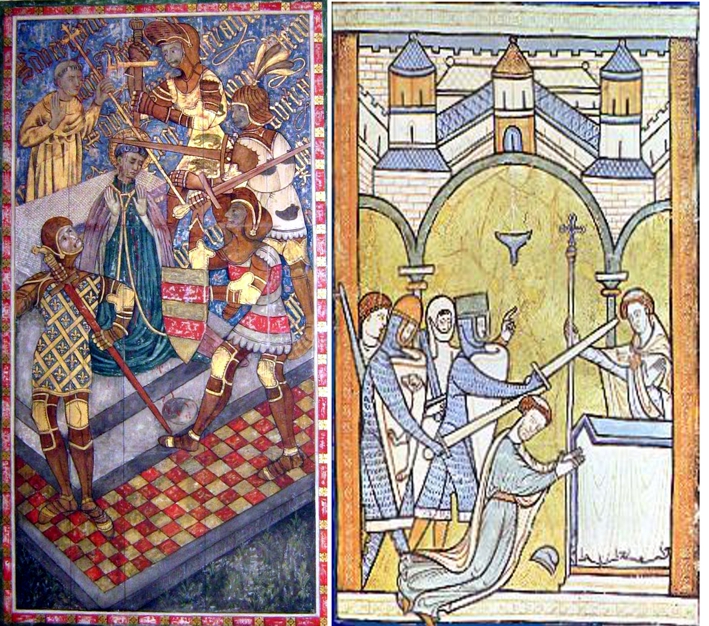

Becket martyrdrom scenes, on the left a boss from Exeter Cathedral

Becket martyrdrom scenes, on the left a boss from Exeter Cathedral

It seemed to me that a general interest in commemorating the eighth centenary of the martyrdom of St Thomas of Canterbury provided an excuse for discussing the meagre heraldry surrounding his murder on the 29th December 1170. Indeed at first sight this paper may appear to be a slight ado about nothing for there is little heraldry associated with the murder of St Thomas of Canterbury and what there is is confused and doubtful. Precisely whether or not a crow did stray into the Cathedral and peck about in the sanguine chaos, staining legs and beak and giving rise to the species pyrrhocorax graculus is not known. Some have it that the chough gained its colouring in like fashion during some Arthurian slaughter half a millennium before. There seems to be a certain problem of carts and horses connected with that of the term beckit. As a soubriquet for the Cornish chough it does not appear in print until the nineteenth century and I can find no official use of the term.[2] The late Hugh Stanford London suggested to me that the pun was achieved by the description of the three choughs sable leggit and beckit gules and the French term bequé in early blazons. No doubt these could be investigated. It is, however, doubtful whether Thomas was called Becket during his lifetime.[3] His father, Gilbert the Brewer and Malt Merchant of London, appears to have had the nickname becket because of his nose and Thomas appears as a’ Becket, son of Becket, in references after his death, presumably to distinguish him from other saints of the name. Indeed, at the Reformation, many churches dedicated to him were transferred to the patronage of Thomas the Apostle.

The arms Argent three choughs proper appear in several Rolls of Arms of the fourteenth century and during the last quarter of the 1300’s in stone and glass in Canterbury Cathedral.

The attributed arms of Thomas Becket, argent three choughs proper

The attributed arms of Thomas Becket, argent three choughs proper

In the fourteenth century the city of Canterbury took as its bearings the attributed arms of St Thomas with a chief of a lion from the Royal Arms of England.[4] There is no surviving patent but this was probably a granted coat. The arms of Thomas were adopted by the hospital dedicated to him shortly after his death which stills stands on the Eastbridge in the city and by other religious establishments under his patronage.

Henry Thomas M.A. of University College, Oxford, who died on the 5th May 1673 bore the same arms as those attributed to the saint, probably without authority, but by Letters Patent dated the 12th May 1564 they were granted to Thomas Penyston. A Crest was granted by Garter Harvey to Thomas Penyston, Lord of Hawrrugge in the County of Buckingham, Esquire, on the 8th July or August in the same year. It seems that the choughs had been anciently borne by the same family for a confirmation of arms and many quarterings together with a pedigree by Thomas Holme Clarenceux was made by Robert Cooke Clarenceux on the 8th February 1573/4. Many with the Christian name Thomas employed the chough allusively in their arms particularly the new grantees of the Tudor era, like Cardinal Wolsey.[5]

The Proclamation of 1538 made it clear that King Henry VIII did not want to see any allusions to Thomas as a saint surviving and evidences, particularly those containing heraldic references, are rare.[6] Little iconography remains and indeed even to this day there is a reluctance to do Thomas the honour due to him as the saint who, in spite of his personal defects of which he was well aware, offered his life and his passion for the things of God against the things of Caesar. Henry VIII knew that in this was a stumbling block to his own carnal ambitions and he had to take the precaution of debunking poor Thomas. I do not intend to go further into the story of Thomas’s life, the politics, the miracles and other matters that led him to be proclaimed a saint by vox populi and to be officially canonised by the Church within three years of his martyrdom.[7]

The Saint’s murderers, Reginald FitzUrse, William de Tracy, Hugh de Morville and Richard le Brito arrived in Canterbury clad “head and body in full armour everything covered but their eyes and with naked swords in their hands”… We know from the words which he spoke, that Richard Brito was in the service of Lord William, the King’s brother. Genealogical investigations show each one of them to have had a connection with the house of Courtenay.[8] These were men of authority and military leaders who, in these early days of the use of coat armory were bound to have identifying insignia upon their shields and probably also upon their surcoats. What little remains of heraldry upon the surviving iconography associated with St Thomas bears this out. Contemporary accounts and near contemporary illustrations of the murder scene identify the perpetrators and show that they were fully armed for battle.

Left: Martrdom of Becket from the tomb of Henry IV in Canterbury Cathedral

Left: Martrdom of Becket from the tomb of Henry IV in Canterbury Cathedral

After the murder the knights collected horses from a house in Palace Street which still stands and, with loot, precious things and certain documents taken from the Archbishop’s palace, they fled to Knaresborough Castle in Yorkshire held by Hugh de Morville.[9] Hugh forfeited this honour to the King three years later being condemned for aiding a rebellion led by the King’s son, Henry. Hugh had been attached to Henry’s Court from the beginning of the reign and was an itinerant justice for the counties of Cumberland and Northumberland. He did penance in the Holy Land and subsequently regained royal favour. His sword is said to have remained at Isell and then passed to the house of Arundel. He was the eldest son of Simon de Morville by Ada, daughter and heiress of William Engaine, through whom he gained the barony of Burgh-upon-the-Sands. Hugh had two daughters, one Ada, married, firstly, Richard de Lucy of Egremont and, secondly, Thomas Multon. The descent subsequently passed through the houses of Gerun and Furnival. The arms generally attributed to this knight were Azure, fretty and flory or, but Azure, an eagle displayed barry gules and argent is also sometimes given for this house.[10]

Arms attributed to Hugh de Morville, Reginald FitzUrse and Richard le Brito

Arms attributed to Hugh de Morville, Reginald FitzUrse and Richard le Brito

William de Tracy had been a close supporter of Thomas when he was Chancellor and after the murder, filled with remorse for his deed, he surrendered himself to Pope Alexander III. He set out on a penitential pilgrimage to the Holy Land but died on the way at Cosenza in Italy. He had supported King Steven against the Empress Maud and had family ties with the royal house. His descendants bore Or, two bends gules but some rolls give Barry or and gules and Or, two bars gules. All figure in representations of the martyrdom.

Reginald FitzUrse had been a tenant of St Thomas when he was Chancellor. He died while doing penance in a religious house near Jerusalem.[11] Bulwich in Northamptonshire was a FitzUrse honour and there was a close family relationship with the house of Brito. Indeed, it would appear that each of the knights had a West-country connection which may have been relevant. FitzUrse was a cousin germane to the King for Syble of Falais, niece of King Henry I, received the honour of Montgomery at the time of her marriage with Baldwin de Bloers. Their daughter Matilda was the mother of Reginald FitzUrse the murderer whose only child, Matilda, married Robert, father of William de Courtenay, founder of Worspring Priory in Somerset. Morville’s descent stems from the lord of Raixall in the same county and passed on to the families of Georges and Blount. Some rolls of arms give FitzUrse Or, a bear sable muzzled argent, other sources two and three bears passant in pale.

Richard de Brito and the malevolent novice of Canterbury, Hugh of Horsey, are said to have committed suicide by the swords they had used but little is known about them. Brito was of the family of Odcombe in Somerset and related to the house of de Warenne whose royal connections are well known.[12] There is no doubt but that Hugh Morville, Reginald FitzUrse and Richard Brito were related. They appear together as witnesses to a deed of Simon Brito or le Bret, brother of Richard and half brother of Ralph le Danys. Le Brito is usually given as bearing three bears’ heads or boars’ heads.

There is no contemporary description of armorial bearings,though by this time there was some use of coat armory among the principal military leaders and territorial overlords.[13] Because of their positions it is likely that these knights were truly armigerous and that the arms shown in rolls and illustrations of the murder are not far removed from what they actually bore. In any event, to the medieval mind responsible for the first portrayals of the murder scene, since knights in the time of the artist bore coats of arms it was inconceivable to believe that their predecessors did not and what more natural sequence of thought than to imagine that they bore the same arms as were borne by collateral descendants of the same families ?

Panels of glass from about the year 1200 in Canterbury Cathedral show scenes of the miracles and among them Thomas kneeling at an altar with the faithful Edward behind him and another with three of the knights in chain mail with basinet headgear hammering at the door. These show no signs of heraldry, but the precise moment in the story is not clear. They wear mail coats only, without surcoats and appear to be unarmed, so the first visit to arrest the Archbishop in his palace could be intended.

From the standpoint of art, the cult of St Thomas can probably be compared only with that of St Francis of Assisi in its swift passage from country to country and its long continuance as a source of inspiration to artists and craftsmen in every conceivable medium. Henry II’s ambitious marriages for his daughters contributed greatly to making the cult more than insular. Joan married William the Good, King of Sicily, in 1177 and in William’s Cathedral of Monreale is to be found the first extant representation in mosaic of Thomas, though the crude stone carvings at Godmersham and other Kentish churches near Canterbury are probably more or less contemporary attempts at portraiture. A chapel of St Thomas was founded in Toledo Cathedral by Henry’s second daughter, Eleanor, the child bride of Alfonso II of Castile and her chaplain, Bishop Jocelyn, founded another in the Cathedral of Siguenza. In these and in the church of S. Maria Tarrassa, north of Barcelona, were late twelfth-century mural scenes from the Saint’s life and martyrdom in which the knights have devices upon their shields. The eldest princess, Matilda, introduced the cult to Germany but, again, I have not personally been able to ascertain what heraldry, if any, may have survived in thirteenth-century murals in Brunswick’s Cathedral of St Blaise or on the Munich mitre.

Several Italian families claim descent from Thomas Becket and his previously exiled kin, as do others in Belgium, France and Iceland. Thirteen churches on the island were dedicated to St Thomas of Canterbury and the cult in Italy was strengthened when the Pope persuaded King Henry to pay for the restoration of the English Basilica of St Paul without the Walls as part of his penance.[14] Wall paintings of the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries there depicted scenes of the life, murder and miracles of St Thomas and early sketches suggest that the knights wore heraldic surcoats and bore the familiar devices upon their shields but following a further fire they have not survived.

The arms of the City of Canterbury still incorporate those of Becket

The arms of the City of Canterbury still incorporate those of Becket

St Thomas of Canterbury, either as a single figure or in his martyrdom, was probably illustrated more than any other English saint in medieval iconography but following Henry VIII’s decree it is surprising that so many examples have survived in whole or in part. At the dissolution of the monastery of Christ Church Canterbury, Will Oldfield, the Bell-founder, was paid 2s 8d to put out Becket and his murderers from the Corporation Seal of the City of Canterbury. He replaced it, either deliberately or through ignorance of the heraldry, with the three choughs arms of the city! The martyrdom scene was found on the Corporation Seal of Canterbury from 1318 and appears on the seals of several Archbishops, the earliest that of Edmund Rich alias Abingdon (1233-1240). These all show the knights as armigerous. The first use of the martyrdom scene on a seal is, however, in Scotland on the first seal of the Abbey of St Thomas at Arbroath, founded by King William the Lion in 1178. Heraldry is not present in this but later a figure of St Thomas was adopted as a supporter for the arms of Arbroath.[15,16]

Among the earliest surviving examples of the martyrdom scene in England are wall paintings and two are of particular interest. One is a painting in the chancel of Preston Church near Brighton in Sussex which was preserved through post-Reformation times by a chalk wash. It suffered considerably during the eighteenth century with other wall paintings when the roof of the church collapsed and they were exposed.[17] Since rediscovery, colours have faded and little remains but the Indian red outline and the original ochre base with slight outline of a bear on one shield. Morville is distinguished by his sheathed sword. Somewhat earlier was the mural found on the wall of St John’s Church, Winchester.[18] The painter clearly knew that the knights were of high enough rank to be armigerous but he gives Morville Azure bezanty and Morville’s own coat is placed on the figure of FitzUrse. Brito is given the arms of a contemporary knight, Sir William de Rye, Azure crescenty, but Tracy has the coat which was borne by that powerful house.

In fourteenth-century representations in the roof bosses of Exeter and Canterbury the full heraldry appears.[19] A few decades later is the splendid panel which remains at the head of the tomb in Canterbury occupied by King Henry IV and his second wife, Joan of Navarre.[20] Here we have a delightful example of the working of the medieval mind in the developed armour and costume. FitzUrse has acquired another bear. On the seal of dignity of Thomas Fitzalan, the contemporary Archbishop of Canterbury (1397-1414), is a representation of the murder.[21] A knight with arm raised and sword about to strike, presumably FitzUrse, is shown with a shield bearing three fishes naiant in pale but this is clearly an engraver’s error.[22] There is another armigerous knight on the same seal bearing a shield bendy, no doubt intended for Tracy who is shown bearing Or, two bars gules, a coat certainly given for members of his house in rolls of arms, in the picture at the head of Henry’s IV’s tomb. About 1370, two hundred years after the martyrdom, we have Sir George Calveley’s Book which is in The College of Arms in London, showing the established coats. [23]

Thomas was quickly acclaimed a Saint and on the 7th July 1220 the body was solemnly translated to the spot in the Cathedral where it became the centre of a Shrine, to which countless pilgrims came for the next three and a half centuries until the Shrine was destroyed and the Saint disclaimed at the Reformation.

The original lecture on this subject was delivered to The Heraldry Society in London on the 4th March 1970.

1 The original lecture on this subject was delivered to The Heraldry Society in London on the 4th March 1970.

2 For the first time as a statement in print in 1967! (Shield and Crest, Franklyn p. 118).

3 He is variously referred to in contemporary documents as Thomas of London, Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas the King’s man.

4 See illustrations in Heraldry of Canterbury Cathedral, Vol. I, The Great Cloister Vault, Messenger (1949) and “County Roll” Soc. Antiques. MS 664. A portrait of King Richard II is set in the western window of the south-west porch and shows the arms of Archbishop Lanfranc alongside those of Thomas impaled by the coat of the archiepiscopal see of Canterbury.

5 Historic Heraldry of Britain, Wagner (1939), illustration by Gerald Cobb.

6 “from henceforth the said Thomas Becket shall not be esteemed, named, reputed nor called a saint, but Bishop Becket… and his images and pictures through the whole realm shall be put down and avoided out of all churches, chapels and other places … erased and put out of all the books”.

7 The story of the martyrdom and the miracles that followed was written down for us within a few days by two monks of Canterbury, William FitzStephen and a certain Benedict who later became Prior of Christ Church, Canterbury, and subsequently Abbot of Peterborough. Their accounts and other contemporary evidences are brought together in two volumes in the Roll Series, Materials for the History of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury.

8 Robert de Courtenay — Complete Peerage sub Devon; Memoirs of Tracy and Courtenay (1796); Arch. J., x (1853); Genealogical History of Courtenay: Cleaveland (1735).

9 Hugh had not struck any blow against Thomas personally. He had stood by the door while the others carried out the deed, keeping the crowd away.

10 Powell’s Roll (c.1350) shows the arms wrongly attributed as are those of Becket.

11 Thus Hovenden but another, somewhat suspect, account suggests that he fled to Ireland and founded the family of McMahon! Tracy’s death was allegedly of some horrible disease of rotting flesh. John of Salisbury has the four murderers dying ignominiously within three years of the martyrdom. On the 12th July 1174 King Henry II certainly did his penance and after walking the length of Canterbury’s city streets barefooted, he bared his back to five strokes of the monastic rod from each of five bishops and to a further two hundred and forty strokes from the monks of Christ Church!

12 The complexities of his relationships with FitzUrse are given in the Victoria County Histories, in English Baronies, Saunders (1964), in a manuscript account of the family held by the Marquis de Meulan who also marks the Courtenay connections and by Collinson, History of the County of Somerset (1791) and in a paper I am preparing for The Genealogists’ Magazine

13 A bear on the shield of FitzUrse shows clearly in contemporary manuscripts, John of Salisbury’s Life (MS. Cotton, Claudius B. ii, fol 341), a psalter also of the last quarter of the twelfth century (MS. Harley 5102, fol. 32), the latter probably also has a fess for Tracy, and in the Life from the Mansell collection on which another shield shows outlines of charges. Two reliquaries in champlevé enamel, one at the Society of Antiquaries, the other at the British Museum depict the murder scene but show no coat armory.

14 Descriptions of the mosaics and wall-paintings associated with the life of St Thomas of Canterbury there are inadequate but what is significant is that Edward III was later to appoint the Abbot of St Paul, co-prelate of the Order of the Garter. To this day, the Abbot surrounds the arms of the Chapter with the Garter and in 1924 King George V took his canon’s stall in the choir of the basilica.

15 Moon and sun symbols signify divine approbation.

16 Until 1539, St Thomas’s figure appears on the Common Seal of the Corporation of the City of London seated between groups of laymen and clergy, while the inscription invokes his protection: Me quae te peperi ne cesses Thoma tueri. There is an empty niche on the Chichele Tower at Lambeth where once stood an effigy of the saint, to which the watermen of the Thames doffed their caps as they rowed their countless barges by. This was the works of John Triske “Magister de les ffremasons” and it cost 33s 3d

17 This work exhibits the height attained in the pictorial representations of the subject of the murder and in order to heighten the degree of sacrilege Thomas is depicted as saying his Mass as his brains are scattered to the ground. The Hand of God blesses the chalice and the faithful Grimm stands on the other side of the altar with the Archiepiscopal cross. What is probably Grimm’s tomb is in the northern crypt beside the spot where the remains of Becket’s bones saved by the monks at the Reformation when the shrine was desecrated, are now buried. On this is a processional cross with the cross in the shape of a round cross formy with central square boss, the prototype of what is now called the Canterbury Cross and was a pilgrim symbol.

18 This was one of the most perfect representations known. The sub-deacon Hugh is not introduced into the picture as he is at Preston. Above the martyr an angel issues from the clouds to receive the saint’s soul and to vest it with the mantel of martyrdom. The colours used are certainly more varied in this painting than was usual during the first half of the 13th century. The scene allegedly of Becket’s murder on the portable altar from Stavelot (Brussels Royal Museum) is in silver gilt, bronze gilt and champlevé enamels dating from the last quarter of the twelfth century. It is of cruder artistry and knows nothing of military armour or symbolism.

19 In the martyrdom bay in the Great Cloister Vault in Canterbury, Morville wears his now familiar coat Fretty and flory, FitzUrse here has two black bears on a white field, Bito bears Argent, three boars’ heads couped azure and Tracy Argent, two bars gules. This, of course, is of late fourteenth century date as the armour suggests and no shields of arms are depicted. The sculpture is exquisite.

20 It is in fact part of my evidence for believing that the tomb was originally intended for Henry’s cousin the Archbishop Thomas Arundel, but that is another story.

21 Item 70 illustrated in the Catalogue of the Society of Antiquaries’ Exhibition of Heraldry at Burlington House, (1894).

22 Heraldry of Fish, Moule (1842) p. 94.

23 What appears to be the original is Harleian Manuscript 1922 at the British Museum which I used rather extensively when studying the heraldry of Henry’s IV tomb more than twenty years ago. Sr. Roger Bryto: Or two bars gules; Sr. Regin filius Ursi: Or two bears sable; Sr. Hug. Morvile: Argent three boars’ heads couped azure armed argent; Sr. Willm Tracy; Azure fretty and flory de lys or.