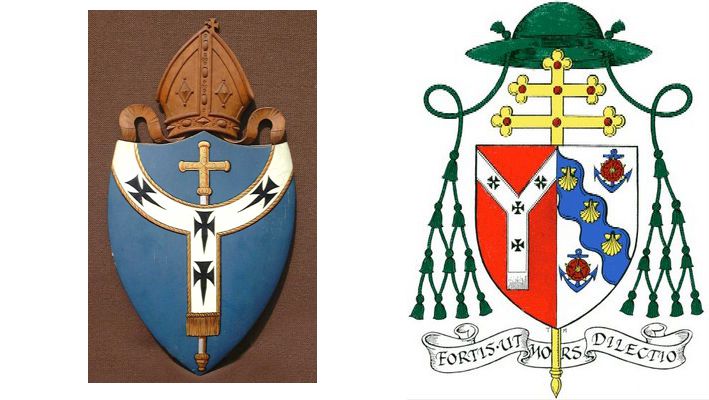

Anglican Archdiocese of Canterbury and Vincent Nichols as Archbishop of Westminster before he became cardinal

Anglican Archdiocese of Canterbury and Vincent Nichols as Archbishop of Westminster before he became cardinal

In the 16th century, with the extinction of the Catholic Hierarchy by Elizabeth I, the titles and coats of arms of the ancient dioceses were assumed by the state nominees. Between then and the accession of James II in 1685 there were no Catholic bishops in England except for eight years under Charles I. In 1685 the first of a long succession of Vicars Apostolic were appointed to govern the Church of England.1 Then, in 1850, Pope Pius IX restored the English Hierarchy and named Westminster as the Metropolitan See.2

Before the Reformation the English bishops generally used two coats, one for the See, (the bishop in his corporate capacity), and his own coat. This practice was not universal, but was, and still is, found in France, Germany and Switzerland. After the restoration of the Hierarchy in 1850 this practice was not immediately resumed, and even to-day it is not the general custom.

Shortly before 1894 Cardinal Vaughan consulted Charles Alban Buckler, Surrey Herald Extraordinary, about the design of a coat of arms for the See of Westminster. He advised the adoption of a differenced version of the ancient arms of the See of Canterbury. The Cardinal then applied to the Holy See, through the Sacred Congregation for Propagating the Faith, which was at that time responsible for the affairs of the Church in England, for a grant of the proposed arms. Pope Leo XIII consented to this and, on the 22nd July, 1894, the Cardinal was able to write to Mr. Buckler from Archbishop’s House :

” You were so kind in preparing a Coat of Arms for the Diocese of Westminster that I am sure you will be pleased to see how completely the Holy See has, in the enclosed Decree, accepted your suggestions in all particulars.”3

The arms so granted and since used by the See are : Gules, an ancient archbishop’s cross in pale Or, over all a pallium Proper. The colour of the field being changed from azure, as found in the arms of the See of Canterbury, to gules in honour of the English Martyrs.4 Before considering the controversy which arose in the early years of this century about the design of these arms it will be well to consider briefly the history of their prototype.

The use of arms by prelates, both for themselves and for their sees, as well as by priests, can be traced back to the 13th century on their seals.5 In England the episcopal seals were more conservatively designed and, generally speaking, coats of arms are not found on them before the 14th century. The arms of the See of Canterbury do not appear until 1349 when they are found on the seal of Simon Islip who was archbishop from then until 1366.6 While they are not found in manuscripts or glass before about 1400 it seems safe to assume that the tinctures have not been substantially altered. The style of the crosses on the pallium and of the processional cross have, however, changed from time to time.

The charges in the coat allude to the archiepiscopal dignity and not, as is more usual, to the patrons of the see. The cross borne before an archbishop, with the pallium worn over his vestments on certain festivals, are the ornaments which distinguished him from other bishops in his province. Further, the date at which the arms make their appearance is not without significance. By the mid-14th century the use of arms had spread through the whole of society; in parts of France even the peasants used seals with arms on them, so that the simple shield of arms was no longer a sufficient token of nobility of the bearer.7 Accordingly ornaments were added to the shield to indicate the rank of the bearer. The earliest of these were the crested helm and royal crown with the papal tiara.8 The other ecclesiastical ornaments used : the cardinal’s hat, mitre, cross and crozier, all seem to follow the same pattern of development. This shows the use first inside and then behind or above are shield.9 In connection with the present inquiry the arms on the tomb of Matteo Cardinal Orsini at Sienna are of particular importance.10 The Cardinal died in 1341 and on his tomb a shield charged with a cardinal’s hat, the strings, without tassels, being knotted together, is placed between two others bearing his personal arms.

In 1897 an interesting letter by Everard Green, Rouge Dragon Pursuivant, to Sir Wollaston Franks, then president of the Society of Antiquaries, was published.11 This discusses the arms of the See of Canterbury and argues that they were the ‘insignia of an archbishopric’ and not those of the see. He bases his argument on the identity of the arms of the Sees of Canterbury and York; church notes in various manuscripts of the College of Arms showing that the field of both shields was originally azure. The same coat, sans tinctures, is found on the seal of John Kyte, Bishop of Carlisle in 1521, (he was formerly Archbishop of Armagh and later titular Archbishop of Thebes), impaled with his own, presumably for his personal dignity. I would suggest that this was parallel to the use of his hat on a shield by Cardinal Orsini. Unfortunately the distinction, between the see and the dignity, was not observed by the compilers of the medieval rolls of arms, who invariably called the arms simply the arms of the bishops of Canterbury.

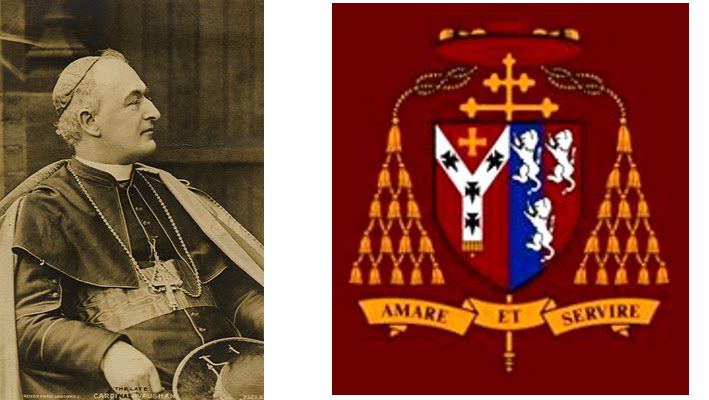

Cardinal Vaughan and his arms

Cardinal Vaughan and his arms

In the papal grant it is specifically stated that the arms granted were ” those which the old Catholic Archbishops of Canterbury used.” The design was therefore quite certain. Unfortunately the advice of Mr. Buckler was not confined to the designing of the shield but extended also to the ornaments surrounding it. Since the Reformation the usages of ecclesiastical heraldry in England had not changed and the introduction in the 17th century of the double barred cross for archbishops, and subsequent extension of the single cross to bishops, went unnoticed.12 Consequently when Cardinal Vaughan went to Rome in 1895 the use of the single barred cross behind, and within, his shield was criticised. Writing from the English College there on 5th February to Mr. Buckler the Cardinal said : “I have been required here to put two bars to the Cross on the Archiepiscopal Shield : it is the universal custom here and they won’t listen to the heralds in this matter.” 13 Certainly this was correct for the cross behind the shield, and his predecessors at Westminster had used such a cross behind their personal arms.

The controversy over this usage within the shield was reopened in 1904 at the enthronement of Cardinal Vaughan’s successor Archbishop (later Cardinal) Bourne. On the 7th March in that year Buckler wrote to Abbot Gasquet that ” on the ceremonial for the enthronement the double-barred cross at the back of the shield is ignorantly repeated thereon?” 14 Earlier in the same year he had written to Archbishop’s House on the same matter and the Rev. W. A. Johnson replied on the 25th February :

” As to the Arms granted to the See of Westminster by Pope Leo XIII June 30, 1894.

The Decree said that they were to be a ” Pallium hanging from the top corners of the shield, on a field gules, divided longitudinally by a gold! archiepiscopal cross ” — ” cruce archiepiscopal de auro.”

If the Decree had said simply ” a gold cross” there might have been some reason for thinking that an ordinary one-barred cross, such as is used in processions, was meant. But the words ” archiepiscopal cross ” we are bound — so it seems to me — to take as meaning a cross distinctive of an Archbishop, and such cross can only be the double-barred one.” 15

Fortunately for us renewed acquaintance with the original grant brought back the ancient design thus demonstrating, in heraldic terms, the historical continuity of the Church in England.

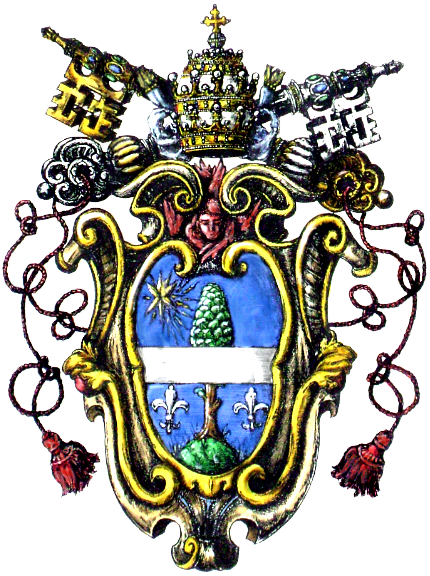

Arms of His Holiness Pope Leo XIII

Arms of His Holiness Pope Leo XIII

APPENDIX

DECREE

The Most Eminent and Most Reverend Lord Cardinal Herbert Vaughan, Archbishop of Westminster in England, made a request to this Sacred Congregation for Propagating the Faith that there should be granted to the celebrated Archdiocese of Westminster as its own arms those which the old Catholic Archbishops of Canterbury used, with the colour of the field changed from blue to red in memory of the Martyrs who, when heresy broke out in England, adorned that Church with their most noble blood. Moreover the very excellent Most Eminent Bishop requested that authority might be granted to him to combine with his own family arms those arms which he was seeking for his Archdiocese.

Then, this request having been conveyed to Our Most Holy Lord Pope Leo XIII by the undermentioned Archbishop of Larissa, Secretary of the Sacred Congregation for Propagating the Faith at an Audience held on the tenth day of the following June, His Holiness graciously deigned to assent, allowing the Archdiocese of Westminster in England to have as its own Arms the sacred Pallium hanging from the upper corners of the shield on both sides, with the archiepiscopal cross of gold in pale, on a red field; and likewise allowing the renowned and Most Eminent Archbishop authority to bear the said Arms in combination with his own family shield, together with the motto Amare et Servire (To love and serve) he then ordered the present Decree to be completed. Given at Rome, at the House of the Sacred Congregation for Propagating the Faith, on the 30th day of June 1894. Locum Sigilli. M(iecislao) Ledochowski (Cardinal Priest of the title of S Maria in Aracoeli) Prefect. A(gostino Ciasca, Titular) Archbishop of Larissa (in Partibus), Secretar

NOTES

- Dom Basil Hemphill, The Early Vicars Apostolic of England, 1685-1750, 1954. Nothing seems to be known about the armorial usages of the Vicars Apostolic before 1829 but almost without exception they were drawn from the nobility and landed gentry.

- By Letters Apostolic Universalis Ecclesiae dated 29th September.

- Brit. Mus. Add. M S 37146, fo. 100. This forms part of a large collection of heraldic notes and drawings made by C. A. Buckler.

- Vide the text of the grant in the Appendix translated for me, from a copy supplied by the kindness of the diocesan archivist the Rev. B. Fisher, by M r . F. S. Andrus.

- D. L. Galbreath, Manuel du Blason, 1942, p. 57, the see of Langres c. 1209-19, P. Sella, I Sigilli del’Archivio Vaticano, 1937, vol. I, no. 278, the see of Beauvais used, in 1245.

- W. de Gray Birch, Catalogue of Seals . . . in the British Museum, 1887, vol. I, no. 1223.

- Galbreath, ibid., pp. 48-58.

- M. Prinet, L’origine du type des sceaux a l’écu timbré, Bulletin arch¬ éologique, 1910; and Armoiries couronées, figurées sur des sceaux français de la fin du X I I I e siècle et du commencement du X I V e , also by Prinet, in Revue archéologique, 1909.

- M. Prinet, Les Insignes des Dignités Ecclésiastiques dans le Blason Français du X V e siècle, Revue de l’Art Chrétien, 1911.

- Rev. John Woodward, Ecclesiastical Heraldry, 1894, p. 137.

- Proc. Soc. Ant., 2nd series, vol. xvi, p. 394.

- Letter by the author in the Coat of Arms, vol. I V , p. 131.

- Brit. Mus. M S 37146, fo. 114.

- Quoted by Shane Leslie, Cardinal Gasquet, a memoir, 1953, p. 176.

- Brit. Mus. M S 37146, fo. 148 et seq.