In this article I propose to review, briefly, the rise of heraldry in Wales, to indicate factors and conditions that have influenced its development, and to suggest lines of research likely to produce a better understanding of a subject that has been for so long to so many a source of wonder and bewilderment.

- Bearers of arms.

The armorial families of Wales consist of three distinct groups, namely, the new arrivals or advenae, the aristocracy of Welsh blood, and the non-tribal Welshmen. The advenae, Norman and English, were of two kinds. The most famous were the feudal lords whose conquering swords brought under their sway wide lands in the Welsh marches: they are sometimes called “Adventurers” in Welsh manuscripts. In their wake came retainers, officials and traders, burgesses of the towns and garrisons of the castles, an immigration that has continued to modern times. One of the earliest-known bearers of arms, the De Clare family, was connected with Wales from an early date, and it is not unlikely that the first heraldic banners to wave over Welsh soil bore the golden chevrons of that baronial house.

The second class, consisting of the royal, noble, and gentle families, forms the backbone of Welsh heraldry. In all, there were some twenty-three royal or quasi-royal dynasties; beneath them came the territorial lords who owned sovreignty within their boundaries; and, finally, a vast network of warrior-farmers with an intense pride in their limpieza de sangre and a strongly-marked local patriotism. Thus, the majority of the nation consisted of a pedigreed population, a distinct caste, whose concept of blood descent has had a direct bearing on the development of Welsh heraldry. The proudest claim was descent from the princes and the great medieval chieftains, over 150 of whom were Heraldic Ancestors, whose significance we shall observe presently. The third class consists of Welsh families whose origins were outside the charmed circle of blood aristocracy, but whose aptitudes and abilities, enabled them to become part of the ruling elite; generally speaking, the heraldry of these families is comparatively free from the complexities associated with that of the preceding group.

- Medieval heraldry.

Welshmen were brought into contact with Anglo-Norman knights in early times, and their medieval heraldry developed along lines similar to that of England. Evidence during the period 1150-1300 is scanty, but sufficient has survived, mainly from seals, to show that arms were used by the more important people, while the lesser folk used personal seals some of which developed at a later date intoarmorial bearings. The earlier Welsh princes and nobles used equestrian seals. Among these, the equestrian seals of Prince Gwenwynwyn of Powys (1200, 1206) and Llewelyn the Great (v. 1222), and of nobles like Elisse ap Madog and Morgan ap Caradog of Afan (both sealed in 1183), Howel ap Howel (1198), Madoc ap Owen (1215) and Madoc ap Caswallon (1231), are notable examples. Armorial seals were not unknown. The seal of Prince David (1246) son of Llewelyn the Great, showed a lion rampant, and Madoc ap Griffith (great-great-grandson of Bleddyn ap Cynfyn) sealed with a similar charge in 1225: John ap John of Grosmont, in 1249, sealed with a lion rampant in a border charged with six escallops. About 1295, David ap Cynwric and Howel ap Meredydd, two nobles from North Wales, sealed, respectively, with a lion rampant, and with paly of six on a fess three mullets. About 1300, Ithel ap Bleddyn bore two lions rampant addorsed, their tails intertwined, with a coronetted maiden’s head as crest — an early example of the use of a crest by a Welsh family.

From 1300 to 1500, a great deal of evidence has survived, showing that arms had become general, and, in some cases, hereditary. Thus, Owen ap Gruffydd (grandson of the above Gwenwynwyn) bore a lion rampant which his daughter carried into the achievement of the house of Cherleton, while another member of the Powysian line, Gruffydd de la Pole sealed in 1310 and 1321 with a similar charge.

We find Leison de Afan (great grandson of that Morgan who had used an equestrian seal in 1183), affixing to a deed about 1300 a seal bearing three chevrons, while his son employed the same device in 1330 with the addition of a Paschal lamb which may be interpreted either as a crest or a conventional decoration — in any case it became the heraldic crest of his descendants. In 1302, Sir John Wogan (descendant of Bleddyn ap Maenarch) sealed with an eagle displayed bearing on its breast a shield charged with three birds on a chief, arms which were borne by his descendants who converted the eagle into a cockatrice crest. Effigies and tomb-slabs, often bearing the names of the deceased on the borders of armorial shields, also indicate the degree of general usage. Poems by fourteenth and fifteenth century bards, valuable genealogical and heraldic records, contain many allusions to the arms of the “native-born”, and one of them refers to the painting of shields on walls, a practice that lingered long, so that in the seventeenth century we still find coats of arms being painted on the interior walls of Welsh country houses.

- The theory of Welsh gentility.

In Wales there was no such being as ” the armigerous gentleman.” The theory was, that a man was gentle by virtue of his genealogy. Gentility followed the blood. This conception of biological aristocracy had deep roots, and it continued to be asserted even as late as the nineteenth century. It is of particular importance to note that the English heralds in Tudor and later times recognised this evaluation of gentility in relation to Welsh armorial claims.

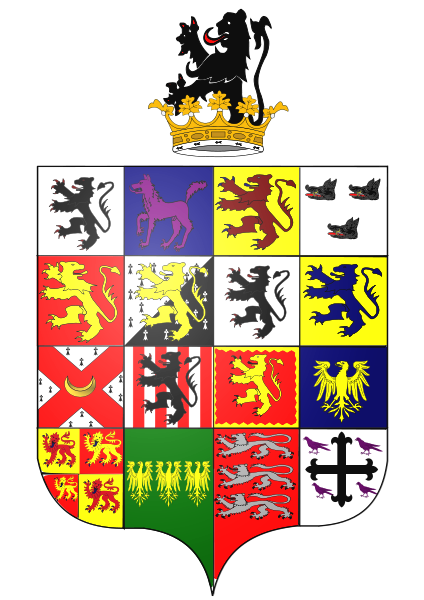

Arms of Hughes of Gwerclas

Arms of Hughes of Gwerclas

- The Heraldic Ancestor.

Although the Welsh had been acquainted with heraldry throughout the Middle Ages, it was not until the early part of the Tudor period that they reduced it to a system. The method employed was ingenious. The bards decreed that all the royal and tribal ancestors should be given coats-of-arms. But what arms were they to be given? Where a family bore arms, the bards stated that, in reality, these had been inherited from a tribal ancestor, and accordingly assigned them to that ancestor. Thus the golden eagles of the House of Gwydir winged their way back from Tudor days until they perched upon the princely shoulders of Owen Gwynedd who had ruled in the 12th century. The arms of the House of Talbot, descendants, in the female line, from the Princes of South Wales, had already, in earlier times, been identified with the southern dynasty; the lions that crouched with their tails curled between their legs on the shields of the fifteenth century Imperial Princes of Wales were alleged to have been derived from one of the coats of Rhodri Mawr who had been king of Wales in the ninth century. All ancestors were to have arms, and coats of many colours were bestowed upon Howel Dda who lived in the tenth century, to Cadwaladr who lived in the seventh, to Cunedda who lived in the fifth, and to Beli Mawr who probably had never lived at all. It was asserted that since a Welshman derived his gentility from ancestors, he was entitled also to derive from them his arms, real or assigned. As large numbers of the ancient stocks survived, showing a remarkable degree of stability, these tribal arms assumed a topographical distribution. The ninety-eight families descended from Urien Rheged, all in Carmarthenshire, bore, in their entirety or differenced, the assigned arms of the said Urien. The hundreds of families descended from Hwfa ap Cynddelw, Cilmin of the Black Foot, Llewelyn of the Golden Torque, Cadwgan Whetter of the Battle Axe, Morgan of the Hound’s Lair, and Rhirid the Wolf, and many other chieftains, all bore the devices that had been assigned posthumously to those worthies. Thus, at one stroke, the bards brought within the heraldic fold droves of wild hidalgoes of the western hills tinkers, tailors, blacksmiths, lawyers, parsons, even paupers, and invested them with a dignity that had hitherto inhered only in their blood. And so was born the idea of the ” tribal ” arms. A Welshman displayed arms because they proclaimed him to be the descendant of some particular ancestor — that was what really mattered. Accordingly, Welsh heraldry acquired a dual purpose. In England a coat-of-arms might be entirely divorced from ancestry; in Wales it was always the result of ancestry. The Welsh coat-of-arms is not merely a mark of gentility — it is the portrait of an ancestor.

But what of families who had borne no arms at all? Lack of imagination is a charge that can be levelled at no Welshman, and none was better qualified in the exercise of that talent than the bard. In such cases arms were invented and described as being the true and undoubted ensigns of ancient chiefs, some of whom had lived in days when woad was the only fashionable blazon.

Furthermore, probably to distinguish between the different branches of a parent stock, we find the emergence of secondary Heraldic Ancestors. A noted descendant of a primary Heraldic Ancestor would be granted his own particular coat, sometimes based on the earlier coat, sometimes entirely different. This practice may have been inspired by the fact that the different branches already bore these different arms when the systematization took place in the sixteenth century. So long as we appreciate the ploy that went on in Tudor Wales we shall be able to understand the principle that governed the acceptance of these coats. They cannot be called fictitious because they were actually borne by Welsh families, but they were most certainly not inherited from the Heraldic Ancestors. It was a present fact converted into a retrospective fiction.

- Control.

The theory that heraldry followed the blood, allied to the rampant individualism of the Celtic temperament, might suggest that an impatient attitude towards control might have resulted. Indeed, it has been observed that Welsh families have shown hostility towards legally constituted heraldic authority. Such, however, is not the case. There is abundant evidence that large numbers of Welshmen flocked to the Herald’s College, especially during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in order to have their arms exemplified, confirmed, or allowed, and, sometimes, to be granted de novo. It is pleasant to be able to say that the College met their claims with sympathy and understanding. An interesting example of Welsh attitude and English practice is provided by the case of Walter Jones of Worcester, a descendant of the princes of South Wales. As his arms were not recorded, he applied in 1603 to Dethick for exemplification and enclosed his pedigree as his sufficient warrant. The action of Dethick is instructive. The great family of Talbot (Earls of Shrewsbury) also bore these arms. Dethick knew this, and he knew also that the Talbot coat was recorded in the College. He was also aware of the Welsh theory of armorial gentility. So he consulted the earl, showed him the pedigree, and asked him whether he had any objection to the arms being exemplified to applicant. Blood, especially Welsh royal blood, being thicker than water, the earl signified his assent, and, thereupon Dethick exemplified the arms to the delighted Walter. The College recognised the special character of Welsh heraldry by appointing local men as deputy heralds, such as Gruffydd Hiraethog and Lewis Dwnn in the sixteenth century, and David Edwardes, Griffith Hughes and Hugh Thomas in the seventeenth.

There were, of course, some who proved leisurely enough about coming to terms with heraldic law. About 1550, the fourth son of Eyton of Eyton established a cadet house, and differentiated, in an interesting and effective manner, the arms of his Heraldic Ancestor, Tudor Trevor. Subsequent invitations to meet heralds for a discussion on the matter fell on deaf ears. Finally, his descendant, William Eyton of Hope Owen, over a hundred years later, on Friday, 22 July 1670, between the hours of 9 and 12 in the forenoon, accompanied by Thomas Harris, a grim bailiff of the Hundred of Mold, presented himself at the Black Lion Inn, Mold, where he found waiting for him two deputies of William Dugdale, Norroy. The business was concluded satisfactorily, and the deputies, Robert Chaloner (Lancaster Herald) and Francis Sandford (Rouge Dragon) were pleased to confirm to him those differenced arms.

Nicholas Parry of Grays Inn, member of an old Flintshire stock, proved to be a heraldic die-hard of similar calibre. He married Anne the comely daughter of Thomas Segar, Bluemantle Pursuivant, son of Sir William Segar a former Garter King of Arms. After a time, Bluemantle began to hint that it might be a sound proposition if the Parry arms were put on a legal footing, particularly in view of his relationship. Despite Bluemantle’s prods, nudges, and growls, Nicholas airily declined to apply for official recognition, although doubtless, the subject of heraldry as an ” in-law ” problem must have given him food for thought. And it was not until two centuries had passed, in 1889, that those arms, slightly differenced, were exemplified to Nicholas Parry’s descendant, who thereby purged the ” offence ” of the ancestor who had been prepared to accept a herald’s daughter but not his jurisdiction.