The display of armorial type devices as depicted on shields and banners has long been considered as associated with the need for ready identification at a distance of the leaders of groups in society, from the Emperors and Kings of sovereign territories down through Princes, Dukes, Earls, etc, to knights and the lords of manors (the origins of heraldry are a different matter and the subject is still open to debate and speculation — see, for example, The Oxford Guide to Heraldry, by Woodcock and Robinson (1988), ch I). The essential difference, as we usually regard it today, between armory and the use of flags, etc, in general from early times lies in the emergence of the continued use of the same device by the heads of successive generations of the original bearer’s family. Once this principle of the treatment of arms as hereditary estate became accepted it soon became the norm, to be followed by the marshalling of a number of individual ‘family’ arms on a shield or banner to indicate a marriage (impalements and inescutcheons of pretence) or various lines of ancestry and inheritance (by quarterings).

The early use of arms to serve as a means of identification to those subject to the bearer’s overlordship and to act as the sign of a rallying point for his forces and supporters in the course of military activity and on peaceful occasions (especially state ceremonies and tournaments) is very rarely encountered today; very few members of the general public could now recognise any personal arms except those of members of the Royal Family.

There is, however, one area where the use of relatively simple designs in a form similar to arms flourishes at the present time and where the use and display thereof is essential for the very purpose of identification, often at a considerable distance, which at one time was met by the display of armorial devices. This is in the field of horse racing where many followers of the sport could instantly recognise the colours of the better known owners. The purpose of these remarks is to compare and contrast both the design of the recognition devices involved and the controls exercised over them by the appropriate authority.

Contests between horses were no doubt arranged by their owners from very early times and probably arose, at least in part, as a result of rival claims as to their abilities. References to such events in the form of chariot races and races between mounted riders occur in the literature of ancient Greece and Rome and it might reasonably be suggested that the various nomadic peoples of Central Asia engaged in riding their mounts in competition to settle wagers from earlier times. It would seem, however, that the sport in a form which we would recognise today first became popular during the reign of James I although Newmarket was then already established as a centre for horse-racing. Since that time many sovereigns and other members of the Royal families have taken a keen interest and continue to participate.

In early races horses would often be ridden by the owner or his groom or stable-lad and it would seem natural for the latter to wear the owner’s livery. As the sport developed and the number of owners entering races rose so would there have been an increasing need for an expanding range of different designs of clothing in order to provide means of identification of the contestants. As in the early days of heraldry, so with horse-racing there would probably have been no control over the adoption by an owner of any design he wished, any clash being dealt with by the organisers of the meeting where it occurred for the purposes of the event in question (such a procedure still operates today in certain circumstances — see below).

As the sport developed so regulatory bodies came into existence, promoted and supported by leading personalities of the turf, to control and administer the activities of racing and to establish rules for the conduct thereof. In Great Britain these functions are enforced by the Jockey Club (founded c. 1750) which originated as a social club for the leading devotees of racing (one meaning of ‘jockey’ in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was one who managed or had to do with horses). For a long time the Club confined its activities to flat racing but c. 1968 it was amalgamated with the National Hunt Committee which had, since 1866, been the independent authority for steeplechasing and hurdling. The combined authority, under the name of the Jockey Club, now supervises all types of horse-racing; it operates a system of licensing jockeys and trainers, controls the organisation of race meetings, lays down rules for the conduct of racing and enforces penalties for breaches thereof, and, of prime importance in the present context, registers colours for race-horse owners to be worn by their jockeys when competing on the course. Similar bodies with similar aims have since become established in other countries where the sport has flourished, eg France (the Société d’Encouragement des Races des Chevaux was founded in 1833), Australia, and the USA.

As suggested above, racing colours probably originated at least in part from owners’ livery colours. Since those early days colours developed along lines which appear to owe much to the ordinaries of simple armory but there are some note-worthy differences between arms and colours. For example, beasts, birds, flowers, and monsters do not appear to have featured on colours; with a few exceptions, designs seem limited to simple geometric devices. Strangely, however, at least two colours which appear in races at the present time feature tartans (for Mr R. J. McAlpine we have the McAlpine tartan for the body of the jacket and yellow sleeves and for Mrs D. Riley-Smith the Henderson tartan with lime-green sleeves) a feature which rarely, if ever, occurs in Scottish, let alone English, heraldry and which hardly lends itself to easy recognition at a distance.

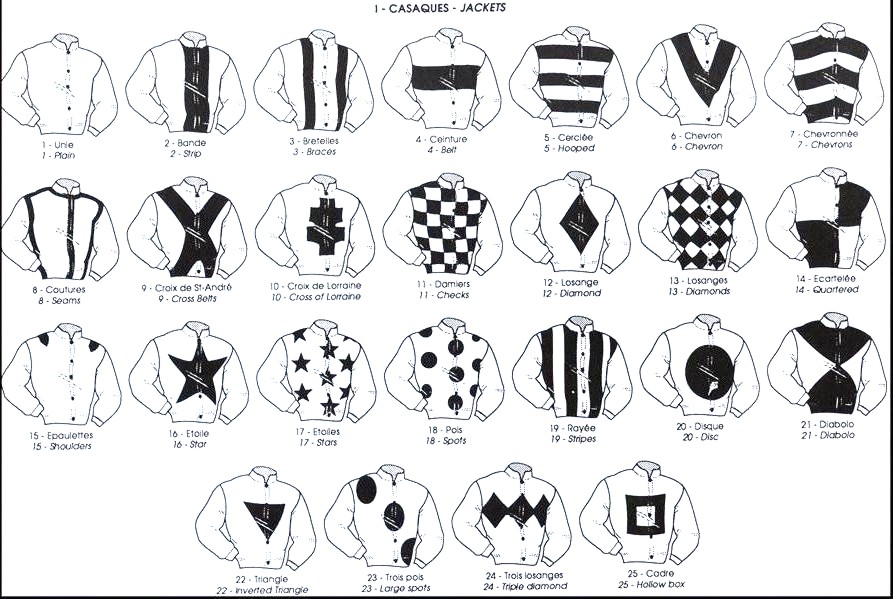

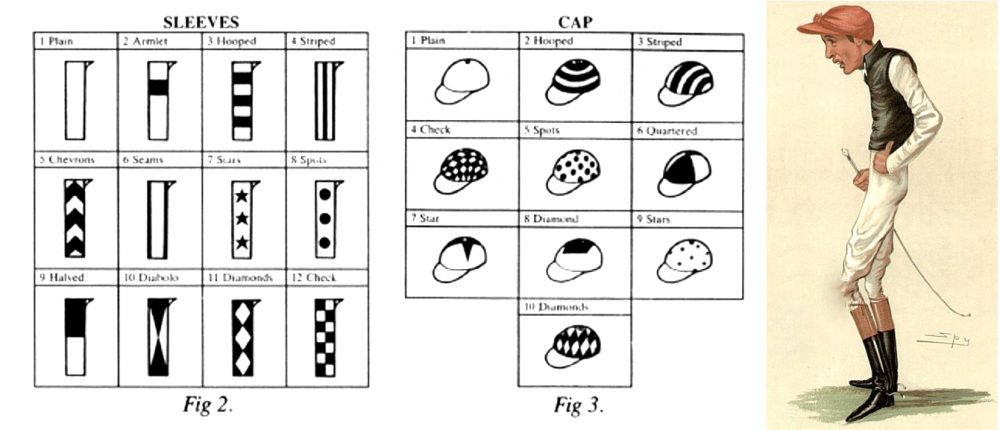

Prior to the early 1970s owners were allowed to register with the Jockey Club any design not already registered. Since that time new applications for colours have had to conform to a specified range of designs reached by international agreement between the various national controlling bodies. Racing colours are comprised of three elements — Jacket, Sleeves, and Cap; the jacket might be compared with the armorial shield, but with the sleeves considered as an elaboration of flaunches, and the cap as a counter-part to the simple forms of very early crests. The permissible designs are illustrated in Figures. 1, 2, and 3 respectively.

It will at once be apparent that nearly all of the jacket designs have immediately recognisable heraldic counterparts, for example: stripe, braces, stripes — pale, pallets hoop, hoops — fess, bars

halved, quartered, diabolo — per pale, quarterly, per saltire

sash — bend sinister (but see below)

cross belts — saltire

chevron — chevron reversed

chevrons — chevronnels

check — chequy

diamonds — bendy-bendy sinister spots — roundels stars — mullets etc.

It is somewhat surprising that whilst the cross of Lorraine appears the simple cross is absent from the approved list. That simple device is, however, often seen on race courses in the well-known colours of Mr Paul Mellon — black, a gold cross — first registered before the restricted lists came into operation. Colours displaying other devices, not permissible under the 1970 Regulations but first registered prior thereto and often seen today, include those of H M The Queen (purple, gold braid, scarlet sleeves); Mrs Miles Valentine (whose charmingly allusive colours are pink, (semy of) cherry hearts); Miss M. Sheriffe (blue, (white) bird’s eye); Mrs C. A. B. St George (white, black chevron hoop — ie a fess dancetty); and Mrs James A. de Rothschild (dark blue, yellow chevron hoops). It is also interesting to find that the outcome of the Scrope v. Grosvenor dispute is echoed some 600 years later in the racing colours of Mr R Scrope (azure, a gold belt); the 1st Duke of Westminster registered his view of the case by his winner of the 1880 Derby being named Bend Or!

Jacket markings must now (and in practice it has generally long been the case) show the approved designs on both the front and back of the garment (note that the sash, going over the left shoulder, when viewed from behind loses its sinister aspect and appears as a simple heraldic bend). One important exception to this practice, which will not arise under the 1970 Regulations, relates to braiding; since this feature presumably had its origin in the ornaments facings applied to military uniforms, it is to be seen only on the front of the jacket; eg Mr John F. Horn — black, white braid. The sleeve and cap designs also feature elements which echo basic heraldic devices.

Associated with the permissible designs is a list of 18 mandatory standard colours. Among these are the basic armorial colours of white, yellow, black, and red; there are three different types of green (light, dark, and emerald) and of blue (light, dark, and royal); the other colours permitted are beige, brown, grey, maroon, mauve, orange, pink, and purple — some of which are found in heraldry, but only rarely. Unlike arms, where some discretion may be exercised by the heraldic artist as to the precise tone and shade in which he paints a given colour, the standard form of application for racing colours states unequivocally that ‘the colours of silks and wools selected should approximate closely to the colours printed’ on the form; there is provision for this requirement to be enforced by the imposition of fines or by the offending owner being required to have the colours remade, if the authorities are not satisfied that the condition has been complied with.

The wider range of authorised colours, albeit with no scope for latitude in their application, together with the lack of any rules as to juxtaposition (compared with the armorial practice of not placing colour upon colour) can lead to racing colours which are not easy to discern in a poor light at any appreciable distance. For example, Mr Athos Christodoulou has orange, maroon disc which seen through a mist or drizzle appears as a uniform reddish jacket whilst Mr D. F. Pitcher has dark blue, light blue cross-belts which in similar conditions appear as an overall intermediate shade of blue; by comparison Mr Paul Mellon’s black, a gold cross shows up well in such circumstances, as does Mr John van Geest’s emerald green, yellow disc.

As might be expected, a number of cases of similarity between racing colours and arms can be found, in addition to the Scrope instance mentioned above. For example, Lord Abergavenny bears the arms of Nevill (gules, a saltire argent) and has for racing colours scarlet, white cross-belts with scarlet sleeves and cap (Lord Rupert Nevill also uses scarlet, white cross-belts for his colours but differenced by white sleeves and cap) and the Duke of Atholl (arms paly of six or and sable) has black and gold stripes with hooped sleeves in the same tinctures. Since racing colours have long been largely restricted by tradition (and since the introduction of the 1970 Regulations by mandate) to simple geometric designs thereby excluding the extensive range of non-geometric charges encountered in armorial usage, the scope for arms/ colours correspondence is very limited.

A recent unofficial development has been the use of the tinctures featured in an owner’s racing colours to decorate any blinkers and trappings worn by his horses.

The Jockey Club is able to enforce its system of granting colours by the requirement that only those owners who have a registration of colours currently operating are allowed to enter horses in races on courses under its control — effectively all courses within the UK. Reinforcement of the Club’s power is provided by a rule which prohibits from entering any race or meeting under its Rules any horse which has competed in any event not run under its authority.

Colours are not hereditable but ‘non-standard’ colours first registered prior to c. 1970 which would not be permissible under the Regulations introduced about that time may be re-registered by a member of the same family even in cases where the registration has been allowed to lapse for many years. In circumstances not covered by this concession (ie all colours which conform with the current Regulations, irrespective of the date of their first registration) it is to be expected that any colours relinquished by the holder for any reason could be re-registered by a member of his (or her) family provided that they had not in the meantime been registered by a stranger in blood. An example of the first-mentioned procedure occurred recently when the 7th Earl of Carnarvon decided to race under the colours used by the 6th Earl, his father, (scarlet, blue collar) rather than those under which he raced before succeeding to the title (Eton blue).

Since each of the various national authorities participating in the 1970 international agreement registers colours in its own territory without considering registrations elsewhere, clashes can occur when owners race their horses outside their own territories. In these circumstances one of the owners involved would be asked to change his colours in some way for the race in question. This requirement would often be met simply by a change of cap (this is also done as a mark of difference when an owner has more than one horse competing in a race — in one recent race a sash was added to the jacket to serve as a further, alternative, such mark).

Acknowledgements: there appears to be practically no published work dealing with the historical background and administrative aspects of the registration of colours; I am, therefore, particularly indebted to Mr Paul D. Palmer of the Jockey Club’s Racing Department for the considerable help he has given me and to the Jockey Club for their permission to reproduce as Figures 1,2, and 3 the illustrations of permissible designs from their Racing Colours application form.